Meanwhile, the regime was eager to fabricate additional “evidence” to justify the arrest of Siarhei Tsikhanouski — while simultaneously laying the groundwork for future charges against Viktar Babaryka and, later, against me. As always, the accusations followed a familiar script: “corruption,” “financial fraud,” “offshore accounts,” and similar clichés. To achieve this, the authorities resorted to a crude, almost theatrical provocation.

During a search of the Tsikhanouski family dacha, law enforcement officers allegedly “discovered” $900,000 in cash, neatly stashed behind the back of a sofa. The absurdity was plain to see: this was already the third search of the same premises. The two previous raids — conducted by the very same investigators, in exactly the same square meters — had turned up nothing. And yet, on this third attempt, a plastic bag stuffed with cash suddenly and “miraculously” appeared. That very day, a criminal case was opened under the article on “illegal possession of funds.”

Plastic bag found behind the sofa

This was not merely an attempt to suggest that anyone who spoke of people’s rights and demanded free elections was, deep down, a fraud or a criminal. The message ran deeper: in Belarus, the law had finally surrendered to the personal interests of one man.

There is no rule of law in Belarus anymore — only the will of a ruler determined to preserve, at any cost, his access to the perks of absolute power. He needs no public opinion, no courts, not even basic logic. What he needs are palaces, monopoly control, and complete impunity.

It was against this backdrop that his earlier remark — “Sometimes there’s no time for laws” — took on a new and ominous meaning. No longer did it sound like a careless slip of the tongue, but rather like a candid admission: laws that obstruct power — and, therefore, personal enrichment — must be discarded without hesitation. The Criminal Code, in this view, becomes what Hegel once metaphorically called “a wax nose” — something that can be twisted in any direction the ruler desires.

The so-called search of Tsikhanouski’s dacha was a shameless display of this new, grotesque system. It was more than a legal violation; it was a public desecration of the very idea of justice. It signaled the destruction of everything taught in universities and academies — where thousands of law enforcement officers were once educated in the belief that they served the law and the people of Belarus, not the whims of a dictator.

For the law enforcement system, this was a turning point. With OMON (the riot police), the lines had always been clear: these were creatures of reflex, trained to respond without thought to the command “attack.” But for those who had entered the profession through law schools and legal academies — those who believed they were guardians of law and public service — this moment marked a profound rupture. Either you followed the law and became a criminal in the regime’s eyes, or you silenced your conscience, forgot the principles of justice, and did whatever you were ordered to do.

Lukashenko — who once worked as a prison guard — understood that the way to break someone’s will was to “bring them low,” to humiliate and dominate. Even those trained to fight crime could be turned into criminals themselves. All it took was the destruction of their professional — and, when needed, personal — dignity.

As Vladimir Vysotsky once sang, “There’s no real difference between truth and lies if you strip them both naked…”

But this was not just personal or psychological violence — it was institutional violence, aimed at the very soul of the legal profession. It turned law enforcers into blunt instruments of repression, transforming practitioners of justice into accomplices of crime. You either obeyed — or you became the next accused, as happened to many who stayed true to their oath of service.

The phrase “no time for laws” became a directive for the entire repressive apparatus — where any norm, from the Criminal Code to the Constitution, could be tossed aside if it threatened the ruler’s grip on power. And the “search” of Tsikhanouski’s home became a public performance of impunity — a chilling signal to every Belarusian who still dared to believe in the rule of law.

The same method was later used against Viktar Babaryka, and eventually against me. Against the banker, the regime deployed its full arsenal of accusations: “corruption schemes,” “capital flight,” “foreign interference.” Around him, they methodically constructed the image of an enemy drawn straight from a late-Soviet propaganda cartoon — the evil “bourgeois” with a barrel of jam and a basket of cookies.

In Belarus today, political competition has been redefined as a criminal offense — with popular support itself serving as the chief “aggravating circumstance.”

The Emergence of Tsikhanouskaya

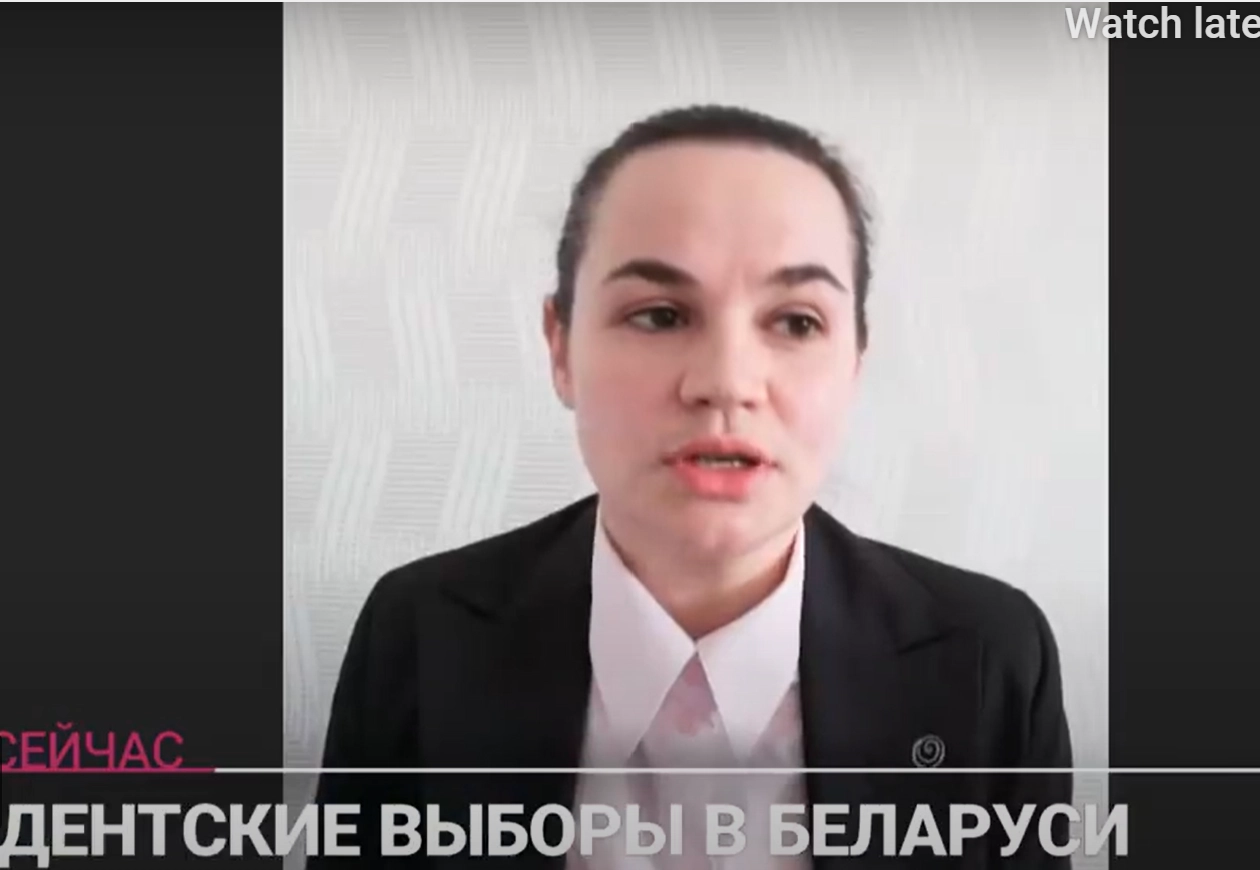

It was at this moment that Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya first appeared in the public space in a meaningful way. With the exception of a brief statement announcing her intention to withdraw from the campaign immediately after Siarhei Tsikhanouski’s arrest, she had only been present as a cardboard cutout at campaign events. But following the "discovery" of $900,000 in cash at their home, she agreed to speak with the Russian TV channel "Dozhd" (Rain).

In that interview, Tsikhanouskaya implied that the money had been planted. Yet it was another part of her statement that would prove far more revealing — and, in hindsight, decisive. She said: “If we really had $900,000, neither I nor Siarhei would have bothered with the so-called rights of the ordinary Belarusian people.”

Belarusians — like citizens of any other country — were unlikely to take a housewife without work experience seriously, especially when it came to politics. This, perhaps, was understandable. It’s hard to imagine that in Germany, the UK, France, or the United States, anyone would truly heed the words of someone who had never held a job, never engaged in public service or collective work, and had no experience in leadership or organizational life. Democracies may differ, but they all share a core belief in competence and accountability — qualities shaped through experience.

Most observers, therefore, simply ignored her remark, focusing more on Lukashenko's methods of political fight. I, too, paid it no attention at the time.

We won’t speculate here on whether Siarhei Tsikhanouski himself shared her view — by then, he was already in prison, unable to comment or dispute such statements. Today, with his release, the opportunity exists to ask him directly. But perhaps, by now, it no longer matters.

What does matter is this: while most dismissed Sviatlana’s comment, one person did not — Alyaksandr Lukashenko. He didn’t hear it as a random misstatement. He heard a confession. A signal of readiness for a deal — any deal — if the price was right. And as we will later see, the price he had in mind was negligible. Barely more than what he spends on food for his dog.

Say what you will about Lukashenko — mock his education, expose the depth of corruption and nepotism that flourished under his rule, lament how Belarus, once among the most promising nations of Central and Eastern Europe, was reduced under his leadership to one of the continent’s poorest. Yet one thing cannot be denied: his political instinct.

It is an instinct honed first among livestock on a collective farm, and later perfected through decades of ruthless power struggles.

We, by contrast, were naïve. We acted on principles. We placed the interests of the people — their freedom, dignity, and right to prosperity — at the heart of everything. That is how a true state must be built. I know that Viktar Babaryka was guided by the same convictions — a man who, like me, risked everything: reputation, property, honor. We did not calculate political gain. We believed in the cause we were fighting for.

It never occurred to me that these principles — the interests of the people — could be traded for a bowl of lentil stew. That someone could enter this campaign not for ideals, but for money.

But Lukashenko grasped it instantly. He heard in that one comment the motivation he understands better than any other: greed — the very trait he has always used to handpick those around him. He knew: people like that are easy to control. They can be bought, manipulated, and held on a leash — by fear, by dependency, or through blackmail.

He may never have read Benjamin Franklin, but he instinctively understood the lesson: “A bag cannot stand upright if it’s empty.” When he heard that careless confession about $900,000, he saw not an opponent, not even a citizen — but a profiteer. A person driven by money, capable of betraying anything for its sake.

And this comment, as we would later learn, became a key factor in his decision to register Tsikhanouskaya as the “opposition” candidate — a convenient, docile, manageable figure. Someone with whom he could stage a carefully controlled performance of elections, offering the illusion of democratic process without any real risk.

To be continued