Lines That Shook the Regime

The Komarovsky Market in Minsk became the birthplace of a new form of Belarusian resistance: the queue. Signature collection points for all three key alternative candidates were set up side by side. People would come to Komarovka intending to sign for their preferred candidate, but often ended up supporting the other two as well.

Some came to sign for Tsikhanouski, then added their names for Babaryka and Tsepkalo. Others came for Tsepkalo and signed for Tsikhanouski and Babaryka. Many came for Babaryka and willingly backed the others, too. This spontaneous overlap revealed an unexpected phenomenon: people who initially supported one candidate ended up backing all three—not out of confusion, but because they genuinely wanted real competition. They wanted to restore the true meaning of the word "election" as a contest of ideas, programs, and competence.

A queue is a social space—and sometimes it becomes much more than just waiting. That was the case in the late Soviet era, when people stood in line for scarce goods. And that was what happened in Belarus in the summer of 2020.

In the USSR, queues were both a symbol of poverty and a place for conversation. While waiting for sausage or shoes, people exchanged news—and discussed politics.

Queues eroded the Soviet system from within. They shattered enforced collective loyalty and gave rise to a human solidarity not sanctioned by the Party or its plans.

The Belarusian signature queues of 2020 became heirs to those Soviet lines—but with different content. People weren’t standing for scarce food or clothing, but for scarce freedom. For hours, in sun or rain, they waited patiently to sign for an alternative candidate and talked about what could no longer be tolerated.

The queue became the seed of civil society. — "You came too?" — "Yes. So I'm not alone. There are many of us." That sense of solidarity became dangerous to a dictatorship that survives by cultivating the feeling of isolation—by making people believe they are alone in their dissent. That everyone else supports the regime.

But the queue destroyed that narrative. It disarmed the regime’s most powerful tool: the fear of being an outsider.

The queue became a new social institution. There were no officials, but it had its own ethics: people let the elderly go first, gave priority to women with children, and helped newcomers figure out where to stand.

When thousands line up not for rations but out of conscience, it is no longer just a queue. It is a form of civic resistance, masked as a bureaucratic procedure. And that made it dangerous.

The Queue at Komarovka, Minsk

Lukashenko couldn’t resist commenting. He called it a "carousel." In a limited sense, he was right: people did sign for one candidate and then queued for another. But it wasn’t fraud, as he tried to claim—projecting his own methods of manipulation, deceit, and public deception onto others. He wanted to convince the public that sincerity was impossible, that people only enter politics for personal gain.

But those in the queue knew better. They knew they weren’t paid. They weren’t Western agents. No one had bussed them in like cattle to stage a fake scene of public support.

The Komarovka queues became the first collective demand for an alternative to one-man rule. People of different affiliations stood together. That blending of supporters across queues became a symbol of true solidarity—the kind that launched the largest protest in Belarusian history, and perhaps in all of postwar Europe.

This emerging unity, first seen at Komarovka, would later take shape in the symbolic "women’s trio"—three women who carried the torch of change after the regime eliminated all the leading male candidates.

The Grodna Provocation: A Signal of Repression

On May 29, 2020, during a peaceful rally in Grodno organized by Siarhei Tsikhanouski, the regime staged one of the campaign's most cynical provocations.

A woman later identified as Yelena Kuzmina, known on the streets as "Lambada," approached Tsikhanouski. On camera and in front of many witnesses, she aggressively pursued him, grabbed his clothes, shouted accusations, and clearly tried to provoke a physical altercation.

Tsikhanouski backed away, trying to avoid contact. At that moment, police intervened. Citing her "complaint," they tried to detain him. During the scuffle, an officer stumbled and fell. That moment was used as the official basis for charges of violence against a law enforcement officer.

Ten people were arrested that day, including campaign coordinator Dmitry Furmanov. All were taken to Minsk and charged with violence against police and organizing actions that seriously disrupted public order.

The provocation in Grodno became a turning point. It made clear that the regime was ready to use any means necessary—provocations, unlawful detentions, fabricated charges—to keep real candidates off the ballot.

Continuing the Campaign

After Tsikhanouski's arrest, only two core team members remained: campaign coordinator Oleg Moiseev, press secretary Maria Moroz, and a handful of volunteers.

At this moment, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya stepped into the public spotlight for the first time. She released a video announcing her intention to withdraw from the race, citing direct threats against her.

In the early stage of the campaign — before she received the support of Veroniсa Tsepkalo and Maria Kalesnikava — Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya communicated with voters exclusively through cardboard cutouts. Siarhei Tsikhanouski did not consider it necessary to invite her to the rallies he organized.

On the day of Tsikhanouski’s arrest, we were holding a rally in Svetlahorsk, in the Homel region. Right in the middle of the event, news arrived of his detention. Almost immediately, Sviatlana announced her withdrawal from the race. In this critical moment, Veronika made the decision to speak out. She became the first—and only—public figure in the country to openly support Sviatlana, calling on our supporters to give her their signatures.

This was truly unprecedented in Belarusian politics. Until then, no candidate had ever transferred their organizational or moral capital to another opposition contender. Competition always outweighed solidarity. Fear of losing influence prevented unity.

Veroniсa’s decision had dual meaning: it was a personal act of civic courage and a precedent for selfless political unification. This would later manifest in the formation of the women's trio. Her brief but decisive message signaled that a new kind of politics was possible—based not on ego, but on trust; not on rivalry, but on shared struggle. A politics where the goal is not personal victory, but collective freedom.

Veroniсa called on our supporters to vote for Tsikhanouskaya. In her next speech, she appealed directly to security forces, invoking their oath and civic duty, demanding they protect the presidential candidate and investigate the threats Sviatlana had reported.

Soon after, officials from the prosecutor’s office visited the school our children attended. They questioned teachers and administrators, trying to gather "evidence" that Veroniсa was an "unfit mother."

This was the first step in a classic repressive tactic: threatening to strip someone of parental rights. It was a direct attack aimed at breaking a woman not only as a political figure but as a mother.

The Signature Collection Phase

Signature collection took place in June, an unusually cold and rainy month in Belarus. This made things harder for campaign teams: volunteers stood outdoors for 10 to 12 hours a day, protecting documents from rain and wind. Makeshift canopies were built over tables; planks laid underfoot; folders shielded with umbrellas. Even a single drop of water, a smudge, or a blurred line could be used to invalidate all collected signatures at a site—electoral commissions had been instructed accordingly.

Despite this, people kept coming. They brought hot tea, coffee, food—to support the signature gatherers in the cold and wet. There was energy and quiet tension at these sites: everyone knew provocations were possible, plainclothes officers were nearby, and cameras recorded not just crowds, but individual faces. Still, people came. They overcame fear and threats. And the regime responded.

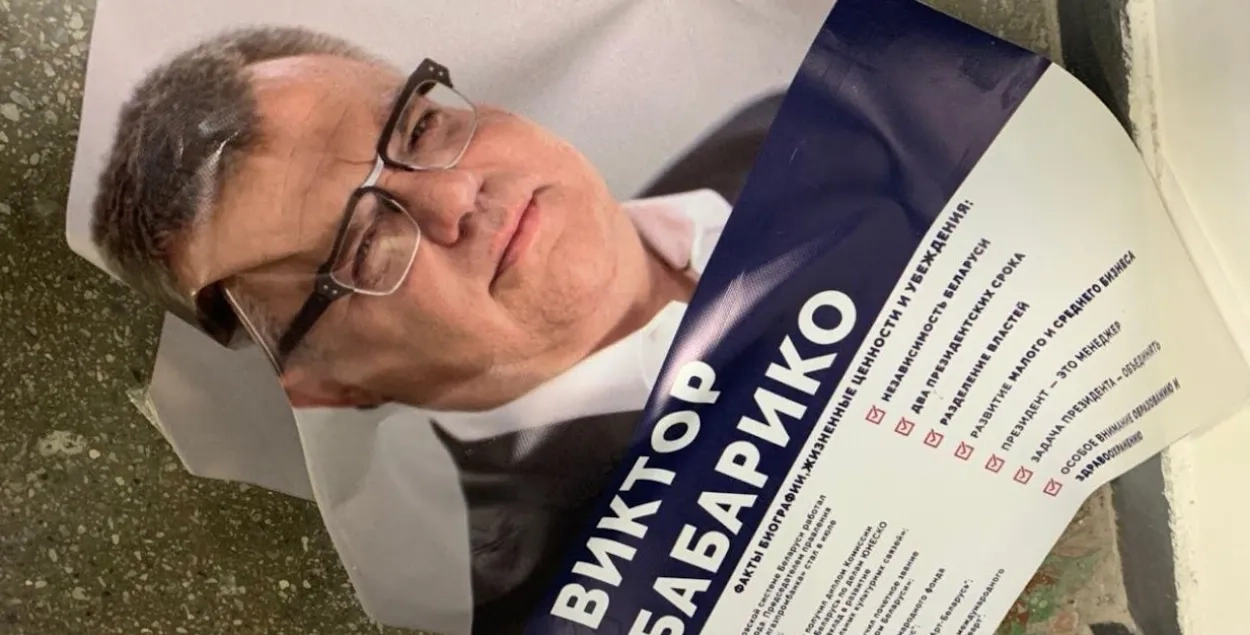

Signature collection for Tsepkalo and Babariko

The Arrest of Viktor Babaryka

Soon came the arrest of Viktar Babaryka, then the leading opposition candidate. The charges were typical of post-Soviet autocracies: tax evasion and corruption. But the absurdity was plain to all.

Belgazprombank, which Babaryka led for over two decades, underwent annual audits—by both the National Bank of Belarus and international firms. Claiming that such a major institution engaged in fraud for years without detection meant discrediting the entire national banking system.

But logic and evidence mattered little. In Belarus, accusations replace proof, presumption of innocence is replaced by propaganda, and investigations follow political scripts. The goal isn’t justice—it’s elimination. Eliminate the rival, demoralize their supporters, and frighten the rest.

Until then, no presidential candidate in Belarus had ever been arrested during an active campaign. There had been disappearances and murders of political figures—Viktar Hanchar, Yury Zakharanka, Pavel Sheremet, Dzmitry Zavadski. There had been post-election arrests—Mikalai Statkevich, Andrei Sannikau in 2010. But a registered candidate, with hundreds of thousands of signatures, arrested before the campaigning stage? Even Belarus had never seen that.

While the regime could frame Tsikhanouski's arrest as removing a "provocateur," Babaryka's detention revealed something deeper: fear. He was detained at the height of his popularity, on track to break records for public support.

This was not just about removing Babaryka from the race. It was about destroying one of the symbols of change. The script was familiar: "corruption," "money laundering," "tax evasion" — a universal set of charges used to neutralize any business figure who stopped playing by the regime's rules.

To be continued