A couple of months ago, I was contacted by a young scholar specializing in comparative political economy and digital transformation issues. He asked me to give an interview about the history of the High-Tech Park (HTP) in Belarus.

Usually, the interviewer introduces the guest. But in our case, it will be the other way around – I will explain why below. But first, let me introduce him. Ildar Daminov is a Kazakh political scientist and social researcher studying the development issues of Central Asian and Eastern European countries. He holds a master’s degree in political science and international relations from the Vienna Diplomatic Academy and conducts research for various international analytical centers and organizations such as the OSCE and the European Commission. My interview was to be part of his doctoral dissertation and a book on comparative political economy and digital development.

Honestly, at this stage, I had no plans to delve into past events in detail. However, this time, I decided to revisit my memories. Not because I feared that certain nuances of my biography, closely intertwined with the history of Belarus, might be forgotten or erased from memory, as the ancient Greeks said, "to sink into Lethe" (lethe in Greek means "oblivion"). Rather, I believe that in a world where human nature remains unchanged, memory and foresight are sometimes the same thing. Therefore, our long conversations were not only about the past but also about the future, which is inevitably approaching. This future is already taking shape in the present – not yet as a certainty, but as a plan of action.

Since Ildar has done significant work on this interview, let it be published in full. What he takes from it for his future book is up to him.

So, let’s begin.

Ildar Daminov: My first question is related to your role as the first director of the Belarusian High-Tech Park (HTP). Your name is often associated with the emergence and subsequent explosive growth of HTP and the IT sector in Belarus in general. You have already described the work of promoting the idea of creating HTP among government officials in your book High-Tech Park: 10 Years of Development. Now, almost ten years have passed since its publication, and I believe your assessment of the development of the Belarusian IT sector today may differ from what you expressed earlier. Please tell us in more detail: how did the idea of creating HTP come about?

Valery Tsepkalo. - I have always been interested in issues of catching-up development, and I first seriously thought about them while studying at MGIMO. An important role in shaping this interest was played by the head of the developing countries sector at the Diplomatic Academy of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs. We met through the magazine Technology for Youth, with which he collaborated. That’s where I submitted my article on the history of medieval knighthood. Seeing my interest in the patterns of historical development of civilizations, he invited me to a meeting at the Diplomatic Academy with former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, who was planning to visit Moscow.

This visit had personal significance for him – the last time he had been in the USSR was in the late 1930s when his father, a Polish diplomat, worked in Moscow. For me, this meeting was not just an opportunity to hear one of the main strategists of American geopolitics but also a gateway into the global discussion on future scenarios for post-Soviet development. Years later, our paths crossed again – this time in Washington, where Brzezinski worked at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). The occasion for our conversation was my article The Remaking of Eurasia, published in Foreign Affairs. In it, I engaged in an indirect debate with him, analyzing possible paths for the transformation of post-Soviet states.

While studying at MGIMO, I specialized in Northern European countries, particularly Finland. Later, while working at the Soviet Embassy in Helsinki, I witnessed the large-scale economic crisis that engulfed the country after the USSR abandoned the clearing payment system. This led to a collapse in Finnish exports and the loss of a guaranteed Soviet market. A wave of bankruptcies began, unemployment rose sharply, and the financial system fell into a deep crisis. Finland, one of the most dependent Western countries on the Soviet market, suddenly found itself without its usual economic mechanisms. However, this shock became a catalyst for reforms.

As one of its key anti-crisis measures, the Finnish government launched a large-scale privatization program covering strategic industries such as shipbuilding, aviation, banking, and telecommunications. State-owned shipyards, including the largest, Masa-Yards, were sold to Norwegian investors, allowing the government to rid itself of unprofitable assets and focus on promising areas of development.

A similar process took place with the airline Finnair – its privatization and listing on the stock exchange helped modernize the company and strengthen its position in the international arena. The consolidation and privatization of banks led to the creation of the largest banking holding, Nordea, which soon became a major player in European and global markets. The transformation of the state telecom operator Telecom Finland eventually resulted in its merger with Sweden’s Telia, forming the transnational giant TeliaSonera.

A crucial step in the reform process was the transformation of the education system. Finland realized that without quality education, building an innovative economy was impossible, and it focused on developing human capital.

Significant investments were made in school infrastructure, class sizes were reduced from 30 to 15-20 students, allowing teachers to give more attention to each child. The country abandoned an excessive emphasis on standardized tests, instead fostering creative thinking, critical analysis, and independent problem-solving.

Teachers' salaries increased significantly, raising the prestige of the profession and attracting young and talented specialists. Teachers received more freedom in choosing teaching methods, making the education system more adaptive and responsive to societal needs.

Parallel to economic reforms, Finland actively developed innovation clusters. The Technopolis network of technology parks played a key role in this process. Initially launched in Oulu, the project later expanded to Helsinki, Tampere, and other cities, becoming a platform for startups, research centers, and high-tech companies.

One of the brightest success stories was the transformation of Nokia. Starting with rubber products, cables, and paper, the company managed to restructure and invest in telecommunications, becoming a world leader in mobile phone manufacturing. Although Nokia was not a typical Technopolis resident, its R&D centers were located in its business parks. Later, when Nokia faced difficult times, Technopolis played a crucial role in preserving Finland’s engineering potential by providing former company employees with opportunities to launch new IT startups.

I later applied this experience in creating the High-Tech Park in Belarus. By analogy with Nokia and Technopolis, I included a provision in the decree establishing HTP that allowed for the registration of business projects. This meant that a company did not have to be an HTP resident or even operate in high-tech industries. However, if it decided to invest in a high-tech project, that new direction could receive the same economic conditions as HTP residents while continuing its main activities.

Another key aspect of the Finnish experience was understanding that a technology park is not just office space but an ecosystem for innovative development. However, I went beyond the Finnish model and introduced the principle of extraterritoriality – an HTP resident company could be located anywhere in Belarus, not just in designated office spaces. This expanded the traditional concept of technology parks and gave companies more freedom in choosing their business locations.

HTP in Belarus developed in a completely different environment – one essentially hostile to entrepreneurship, freedom, and a culture of risk-taking. Its rapid growth continued until it became a major factor in the Belarusian economy, generating billions in revenue and high salaries, only to be viewed as another "cash cow" for the off-budget "presidential fund."

I.D.: We’ve digressed a little. After all, the historical distance between your work at the Soviet embassy in Helsinki and the creation of the High-Tech Park is quite significant. Moreover, Finland is far from the only country that realized the need to build a "knowledge economy" to overcome backwardness and emerge from economic and social crises. In fact, it may have had an easier time than many others. After all, it was in Europe, and its closest neighbors—Sweden, Norway, and Denmark—were highly developed countries. Even during its period of strong dependence on the USSR, Finland, unlike the member states of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA—the economic union of the so-called "socialist camp"), maintained a market economy and a developed industrial sector, which gave it a much better starting position.

V.T.: Yes, you’re right—perhaps I have given too much attention to the Finnish experience. But please understand—for me, this was not just an academic interest. Finland left a deep emotional imprint on me. I learned its language, and with it, I grew to love its culture and people. It became my gateway to life; I learned a lot from scratch there. Accompanying Soviet delegations to Finnish enterprises, I thoroughly studied the country’s industry, gained a solid understanding of its economy, and grasped the challenges it had to face.

After one of these visits, a decision was made to include a tour of the Nokia company in the official itinerary of Mikhail Gorbachev's visit to Finland. Later, when I visited Finland again as the head of the High-Tech Park, the first vice president of Nokia—by then the world leader in mobile phone production—gave me a book on the company’s history. In it was a photograph of Mikhail Sergeyevich, amazed by his first wireless call to his Kremlin office. His secretary answered his call, and his eyes literally widened in surprise.

We will return to Finland later when my knowledge of the language and the country helped attract the largest Finnish-Swedish IT company, Tieto (which means "knowledge" in Finnish), to the Belarusian High-Tech Park. The company specializes in developing banking software. But for now, let’s get back to the main narrative.

After the collapse of the USSR, I decided to return to Belarus and joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to contribute to shaping the independent foreign policy of the new country, which I had always considered my homeland. At the time, I actively published articles on modernization, foreign policy, and constitutional reforms. In addition, I hosted a weekly radio program, Belarus and the World, where I analyzed international affairs, global economic trends, and issues related to modernization and catch-up development.

Soon, I was personally invited by the Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Belarus, Stanislav Shushkevich, who offered me the position of advisor on foreign policy and foreign economic relations. While working at the Supreme Council, I wrote a modernization pamphlet, The Way of the Dragon, where I outlined my vision for structural reforms and innovative development, drawing inspiration from the successful experiences of Asian countries—Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

Extrapolating their achievements, I briefly mentioned mainland China as well, seeing enormous potential in its development. However, in 1994, such predictions seemed highly improbable to many—China was mostly viewed through the lens of jokes, and few seriously discussed its economic prospects. In fact, the mention of China in my work attracted the most criticism and ridicule.

Yet, to me, it was obvious that China would "take off" in the coming decades. Deng Xiaoping carefully studied Singapore’s experience, learning extensively from its leader, Lee Kuan Yew, and adopting the concept of industrial parks, special economic zones, and later, technological clusters where market mechanisms and favorable conditions for foreign companies thrived. It was clear that if the ethnic Chinese populations of Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong had succeeded, then China itself would also succeed.

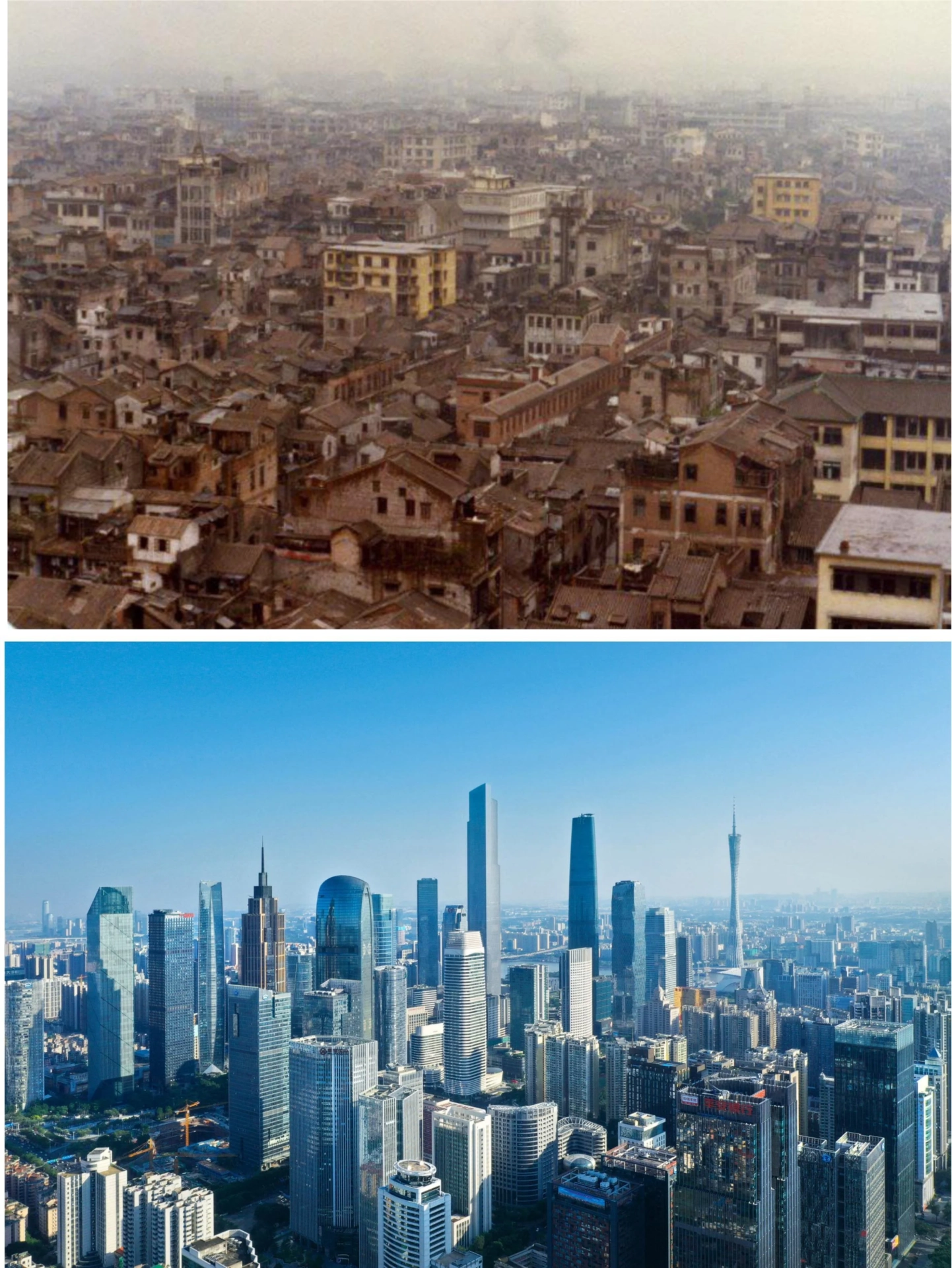

Later, in 1992, the Chinese leader embarked on his famous Southern Tour, visiting Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Shanghai, which kickstarted the rapid development of industrial clusters and the attraction of foreign investments. During that time, Deng proclaimed principles that became the philosophy of China’s modernization: "It doesn't matter whether a cat is black or white—as long as it catches mice," and "Those who get rich first will help others," which effectively encouraged entrepreneurship and recognized private property rights.

Guangzhou, China in the early 80s vs. today

I was convinced that a combination of state strategic planning and market mechanisms, successfully tested in Asia’s "economic tigers," could be the key to Belarus’s rapid development as well. At the core of this model had to be an innovation system that created favorable conditions for the emergence and growth of high-tech companies. Integrated into the global economy, they would not only thrive in exports but also strengthen the country's intellectual and scientific potential, positioning Belarus as a hub for global technological development.

This was the path I proposed for Belarus—a path that would have ensured rapid economic growth, the creation of modern infrastructure, sleek offices for cutting-edge companies, comfortable housing, modern hotels, sports and playgrounds in every neighborhood, the development of small and mid-sized towns, the construction of community centers, and most importantly, a significant increase in people’s incomes. This path would have placed Belarus among the global leaders in innovation and technology.

We all know that this did not happen. The real question is: Was the country’s economic stagnation, industrial decline, agricultural collapse, rural depopulation, and widespread poverty the result of incompetence or a deliberate choice by the country’s leadership?

To be continued.