Continuation.

The beginning - Belarus HiTech Park. Memories of the future.

Ildar Daminov: As far as I know, after the resignation of Stanislav Shushkevich, you transitioned to a new role…

Valery Tsepkalo: ...at the Executive Committee of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) as a senior advisor to the Executive Secretary. Although my tenure there was brief, it was quite fascinating in its own right. We organized meetings for presidents, prime ministers, and key ministers, preparing their agendas. At that time, the atmosphere was notably amicable—despite the fact that countries were primarily engaged in dividing up the post-Soviet legacy. Many of the meetings had an informal, even cordial tone. I could share numerous interesting anecdotes, but they would not be particularly relevant to our current discussion.

I.D.: Alright, let’s get back on track. Finland surely wasn’t the only country that pursued modernization during a crisis?

V.T.: Of course not! When I served as First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, my role was not just to maintain cooperation within the CIS framework but also to cultivate relationships with distant countries. In Asia, India, and the Middle East, I met with politicians, scientists, business leaders, and ordinary citizens.

At the time, the standard of living in these regions remained relatively low—industry and technology were not yet developed to the extent they were in our part of the world. Yet, what struck me most was their unwavering confidence in the future. There was an overwhelming atmosphere of optimism. People genuinely believed that tomorrow would be better than today. They witnessed change unfolding before their eyes. Take Singapore, for instance—it took just one generation, 25 years, for the country to transform from a port-based labor economy into a global financial hub.

Effective governance, investment in human capital, a commitment to attracting foreign investments, development of high-quality infrastructure, and the establishment of a favorable business climate—these were the key ingredients that allowed Southeast Asian nations to overcome economic stagnation and reach the level of developed Western economies.

Consider Malaysia: 30 years ago, its GDP was $45 billion, comparable to that of Belarus. By 2024, Malaysia’s GDP had soared to $400 billion—nearly six times that of Belarus. Singapore, whose GDP was once lower than Belarus’s, today boasts an economy exceeding $500 billion, despite having a population of just 5 million. That is more than seven times the economy of Belarus, which has a population of 9 million. Meanwhile, over the past three decades, Belarus’s population—despite the absence of war—has declined by 1.1 million. Unlike Singapore, however, Belarus possesses significant natural resources.

But let’s return to history. Their optimism was not only inspiring but also created a sense of stability—though not in the traditional sense. For them, stability did not mean an absence of change but rather a continuous flow of transformation that propelled society forward. This was reflected not just in rising wages and improved living standards but, more importantly, in better working conditions—a shift from low-skilled, physically demanding labor to high-tech professions: IT engineers, bankers, and researchers. This development-driven optimism was far more compelling than any political slogans about “traditional values” or “spiritual bonds.”

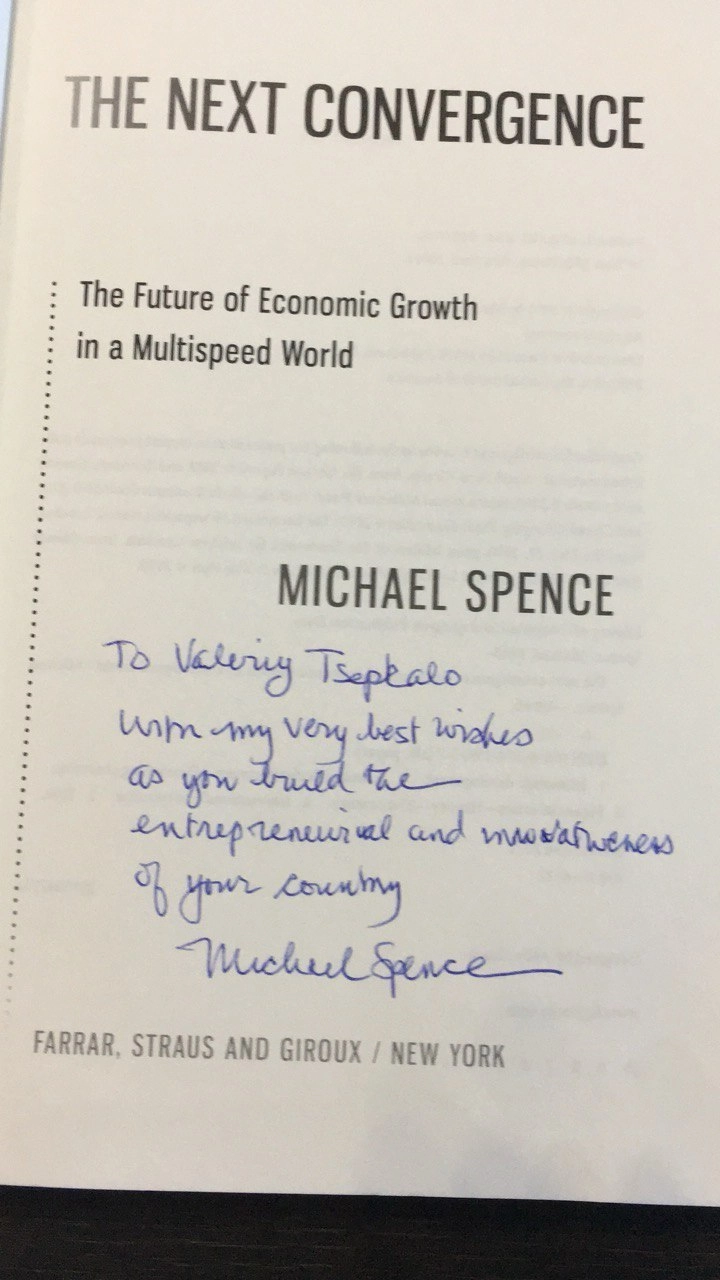

Of course, such progress required bold political decisions. As Nobel laureate in economics Michael Spence, who advised the South Korean government, told me, it took immense political will. In the 1980s and 1990s, much of South Korea’s economic growth was driven by light industry—producing a significant share of Europe and the U.S.’s sportswear and footwear. This sector provided jobs and stable incomes. Naturally, political elites were tempted to maintain this model since it was already yielding success.

However, South Korea’s leadership made a decisive shift toward high-tech industries. Light industry, though profitable, became an obstacle to progress; it trapped a large portion of the workforce in low-value-added jobs, preventing them from retraining for emerging fields. The government’s strategic pivot towards high-tech sectors—mechanical engineering, microelectronics, shipbuilding, and IT—was the catalyst for South Korea’s economic breakthrough.

Singapore offers another compelling example. At my request, they later organized a seminar on managing and constructing technology parks, based on the Singapore Science Park, which specialized in R&D for local and international IT firms. Unlike many nations that cling to outdated industries, Singapore never sought to “save traditional manufacturing”—a symbol of economic stagnation. Instead, they transformed an old textile factory into LaunchPad, an innovation cluster that became the heart of Singapore’s startup ecosystem, housing over 100 startups, venture capital funds, and tech incubators.

LaunchPad Singapore

Perhaps the most remarkable decision was Singapore’s move to essentially push Toyota’s factory out of the country. Singapore’s visionary leader, Lee Kuan Yew, believed that low-value assembly-line manufacturing did not align with the country’s strategic goals. He argued that labor and intellectual talent should be utilized more efficiently.

Why am I highlighting this? Because Belarus did the exact opposite. The government supported industries with no long-term market potential—labor-intensive, energy-consuming sectors that effectively entrenched economic stagnation and stifled progress. A prime example is the Motovelo factory, which was repeatedly propped up with enormous financial injections despite its poor market prospects. Unlike Asia, where warm climates and high urban density sustain strong demand for motorcycles and bicycles, Belarus simply lacked a viable market for these products.

Misguided financial subsidies that could have been directed toward education or infrastructure were instead wasted on futile attempts to “rescue” outdated factories such as Horizon, Vityaz, Integral, and many others. Rather than being privatized and integrated into major international corporations, these enterprises continued to drain colossal financial and human resources with no hope for sustainability.

Ordzhonikidze Factory Gate, Repeatedly Rescued by Government Subsidies

I.D.: I understand that a thriving tech sector requires a supportive business ecosystem. In my doctoral dissertation, I plan to focus on the development of technology clusters in authoritarian regimes—this will be the central theme of my research.

V.T.: I would distinguish between authoritarian modernization and technology cluster development under authoritarianism. While both involve technological sector growth despite restricted political freedoms, they differ fundamentally. The former refers to state-driven modernization and economic development imposed from above.

Take South Korea, for example. The government not only supported businesses but also mandated corporate reinvestment in high-tech sectors. A historical comparison can be drawn with Nokia in Finland, which began as a rubber products manufacturer before transitioning to mobile phones. In Korea, however, this kind of business transformation was a matter of state policy: corporations received government support but were also required to invest in promising industries. The results were astonishing.

Samsung, originally an exporter of dried fish and noodles, later ventured into textiles, construction, and shipbuilding before evolving into a global leader in electronics (TVs, then mobile phones) and memory chips. Hyundai, which started as a construction company, shifted into automobile manufacturing and later founded Hynix, now the world’s largest producer of NAND memory and chips used in Apple, Dell, HP, Lenovo, and Sony products.

We successfully attracted Hynix to the High-Tech Park, where it specialized in chip design. The average salary for its few hundred Belarusian employees was around $5,000, a stark contrast to young engineers at Integral, who earned barely $300 due to the factory’s outdated business model.

The Belarusian branch of Hynix had the potential to become one of the company’s key hubs, with plans to expand its workforce to several thousand employees, particularly after acquiring Intel’s chip manufacturing business for $9 billion. However, the events following 2020 forced Hynix, along with hundreds of other companies, to withdraw from Belarus, crushing any remaining hope for the revival of the country's microelectronics industry.

LG also underwent significant transformation, and we had the opportunity to visit its factory. Initially, the company specialized in the production of detergents and budget cosmetics but later transitioned into manufacturing televisions, mobile phones, refrigerators, and air conditioners.

In South Korea, technology parks developed organically, with Daedeok Innopolis standing out as a prime example. This cluster reminded me of the USSR Academy of Sciences, but with one crucial distinction—besides research institutes and design bureaus, it also housed corporate R&D labs specializing in IT and biotechnology.

I was particularly struck by Korea’s ambitious approach to biotechnology. The country invested heavily in cosmetic product manufacturing, establishing dedicated research institutes for studying ginseng and developing high-end skincare products, including creams, lotions, and toothpaste. Over time, this sector evolved into genetic-based cosmetics tailored to DNA analysis, peptide production, stem cell research, and cutting-edge UV filters. Daedeok was also where code division multiple access (CDMA) technology was developed, forming the foundation of 3G mobile communication. Additionally, the park made significant advancements in robotics, including humanoid robots, autonomous drones, and sophisticated surgical systems.

Yet, in Korea, technology parks did not drive modernization to the same extent as in Taiwan, Singapore, China, and India. Taiwan, for instance, deliberately focused on specialized technology clusters from the outset. I visited Hsinchu Science Park twice—it became the heart of microelectronics and IT product manufacturing. The park is home to global tech giants such as TSMC (the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturer), ASUS (a leading producer of motherboards, laptops, and smartphones), Acer (a major manufacturer of laptops and PCs), and HTC (a pioneer in smartphone and VR technology). We successfully attracted HTC to the Belarus High-Tech Park (HTP), helping Belarus establish one of Europe’s strongest capabilities in mobile software development.

TSMC - Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

These examples illustrate how governments can foster innovation and technology growth through a combination of incentives and strategic intervention, as seen in Korea. However, Belarus’s case of “authoritarian modernization” was an entirely different story—the High-Tech Park in Belarus was forced to develop in a business-hostile environment.

I.D.: Let’s delve deeper into Belarus’s experience. You mentioned Mahathir Mohamad, the architect of modern Malaysia, who transformed the country into one of the “Asian Tigers” during his 21-year tenure. Malaysia achieved remarkable economic success under his leadership! How did he implement authoritarian modernization?

V.T.: Mahathir undertook a series of groundbreaking initiatives, many of which are detailed in his book "The Way Forward", which I translated into Russian, wrote a foreword for, and published through AST. However, I believe you’ll find his personal insights even more intriguing.

One of his most ambitious projects was the creation of Cyberjaya, a technological hub envisioned as an Asian counterpart to Silicon Valley. The aim was to attract leading global companies and build a thriving innovation ecosystem. To demonstrate the government’s commitment to the project and make a strong impression on the global business community, Mahathir situated Cyberjaya near the newly constructed capital, Putrajaya, located 20 km from Kuala Lumpur to alleviate urban congestion.

To attract world-class companies, Mahathir took a bold and unconventional approach—he constructed state-of-the-art office buildings and essentially offered them for free to businesses that agreed to establish operations in Cyberjaya. His reasoning was straightforward: “Any country can build office spaces—that’s easy. But turning those buildings into epicenters of technological innovation is a far greater challenge.”

Cyberjaya, Malaysia

His approach was simple: Companies that set up operations there paid only for utilities. After 20 years, the buildings became their property. During this period, corporations such as Microsoft, Motorola, and IBM established training centers at universities, hired and trained local talent, and became deeply integrated into the business ecosystem, making it difficult for them to leave.

Incidentally, I invited Dr. Mahathir to join the International Advisory Council of the Belarus High-Tech Park, and he remained one of our most esteemed international representatives for many years.

With Dr. Mahathir Mohamad

I.D.: Could Belarus have implemented a similar strategy?

V.T.: Honestly, we could only dream of such favorable conditions for the tech industry in Belarus. Initially, I fought to establish the High-Tech Park near the National Library. Firstly, it had a metro station, which would have facilitated student commutes—allowing them to work in company offices while enabling professionals to easily access universities for lectures and research collaborations.

Secondly, I believed a prominent architectural project at the city’s entrance would attract potential investors, including foreign business leaders visiting Minsk. For instance, Microsoft president Steve Ballmer, whose parents were Belarusian immigrants, visited Belarus solely to pay respects at his ancestors’ graves. A visually striking technology park at Minsk’s gateway could have served as a “living advertisement” of the country’s technological potential, sparking investor interest.

Lastly, the National Library could have greatly benefited—becoming a hub for seminars, conferences, and meetups, fostering intellectual engagement rather than merely storing printed books and periodicals.

However, this prime real estate was already claimed by Serbian developers, the Karić family, who had no interest in Minsk’s technological or aesthetic development but managed to convince decision-makers that they could generate quick profits. As a result, we were assigned a much less desirable site—an area occupied by abandoned buildings from the Belarusian Academy of Sciences and the city’s snow dump.

I.D.: The development of the High-Tech Park’s location warrants a separate discussion, but let’s return to your reflections on Asia. You described an atmosphere of energy and optimism, but we know that not everything was smooth. South Korea experienced violent student protests and police crackdowns, and China, of course, faced the tragic events of Tiananmen Square.

V.T.: That’s absolutely true. In the 1980s, student protests were widespread across South Korea. The government of Chun Doo-hwan brutally suppressed demonstrations. However, the rise of the middle class and growing demands for government transparency eventually led to democratic reforms in the early 1990s. The student movement played a pivotal role in South Korea’s transition to democracy.

Meanwhile, China’s economic expansion, initiated by Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, cultivated a new generation that aspired to more than just economic stability—they sought political change as well. This culminated in the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, posing a major challenge to the Chinese leadership. However, despite the crackdown, China continued its modernization push, doubling down on technology-driven growth and market liberalization—which we previously discussed.

Economic progress often fosters the emergence of a new middle class eager for political participation. This sometimes triggers calls for wealth redistribution, which, in turn, can fuel xenophobic sentiment—as seen in Indonesia and Malaysia, where resentment toward ethnic Chinese business communities occasionally erupted.

I.D.: Do you see xenophobia as an inevitable byproduct of economic development? Why does this happen? Shouldn’t an expanding economy foster interethnic and interfaith harmony?

V.T.: In the long run, that is true. However, development always comes with challenges. In those years, Asia experienced intense anti-Chinese sentiments, similar in nature to the antisemitism seen in 1930s Europe. These tensions arose as national industrial capital began competing with transnational forces.

Historically, Chinese communities in Asia have held dominant economic positions, controlling major sectors of trade and entrepreneurship—much like Jewish communities once did in Europe and America’s financial and commercial sectors.

This dynamic was not solely about trust within their own communities. In Europe, Jews from England, Germany, and France often felt a closer affinity with each other than with their non-Jewish compatriots. Similarly, in Southeast Asia, Chinese communities in Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia had stronger internal ties than with the local populations. More importantly, both Jewish and Chinese communities were historically excluded from politics and other spheres, compelling them to concentrate on business.

It is important to understand that the economic dominance of minorities is often shaped by the political system. Ruling elites frequently entrusted sensitive financial and trade responsibilities to national minorities. Why? Because these groups, lacking significant electoral influence, were not seen as political competitors. They could be allowed financial control without posing a direct threat to the political status quo. This strategy minimized the risk of new power centers emerging within the dominant ethnic group.

In Malaysia, Chinese communities coexisted peacefully with the local population—until democratization began. Lee Kuan Yew was on the verge of leading not only Singapore but the entire Malaysian Federation. However, as Chinese political influence grew, so did anti-Chinese sentiments, ultimately leading to Singapore’s expulsion from the federation. Many believed that without its own natural resources—not even fresh water—the city-state would be doomed. Yet, as history has shown, Singapore not only survived but emerged as one of the world’s leading economic powerhouses.

During modernization, national elites, upon gaining economic independence, often viewed the dominance of ethnic minorities as unjust. They sought to redistribute resources in favor of the titular nation, which frequently led to xenophobia. Fortunately, Singapore, as a "Chinese enclave," found a far more constructive solution than the Jewish ghettos of Europe.

Despite these challenges, over time, as economies expanded, national capitalists became wealthier and found it beneficial to collaborate with ethnic minorities. Eventually, a balance was struck that served both sides.

This trend is universal and not confined to any particular historical period or geography. Consider Henry Ford’s early career in the United States—he initially opposed Jewish financial influence, seeing it as a threat to his company’s independence. However, as Ford’s business grew stronger, he revised his views and ultimately collaborated with those he once criticized.

A compelling example is my friend Wong, an ethnic Chinese businessman in Malaysia. He owns a luxury car dealership and successfully navigated ethnic policies by marrying an ethnic Malay woman, thereby circumventing the legal requirement to employ a Malay director. This illustrates how, in complex ethnic systems, entrepreneurs adapt, aligning their business interests with local laws and traditions.

I.D.: How do you compare the situation with interethnic relations in these European and Asian countries?

V.T.: I would emphasize that the decline of Jewish political and economic influence in Europe was not solely due to the Holocaust, but also to the establishment of a Jewish national state. The Jewish people redirected their energy toward building Israel—literally from the ground up, in a desert. The most driven and visionary members of the Jewish community committed themselves to this endeavor, enduring wars, hardship, and immense effort to realize their vision of a sovereign homeland.

In some ways, Singapore's story parallels Israel’s history—or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that Singapore’s trajectory mirrors elements of Israel’s experience. Both nations faced a lack of natural resources, a challenging climate, and persistent geopolitical threats: Israel, surrounded by hostile Arab states; Singapore, squeezed between an unfriendly Malaysia that had expelled it and a vast Indonesia, where anti-Chinese pogroms were frequent. Yet, both nations not only survived but thrived by prioritizing science, technology, and innovation, ultimately becoming two of the most advanced economies in the world.

Their similarities even extended to military strategy. Inspired by Israel’s decisive victory in the Six-Day War, Singapore enlisted Israeli military advisors to help build its armed forces. One of the key figures in this effort was Shimon Peres, a Belarusian-born Israeli statesman who, at the time, served as Deputy Minister of Defense.

I had the privilege of meeting him twice. The first time was at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, in Minsk, when he visited his hometown of Volozhin, where he had lived until age 15 (then known as Semyon Persky). The second meeting took place during his official visit to Washington in the early 2000s, when I was serving as an ambassador. Our conversation was lengthy, though unrelated to this particular topic.

While Malaysia and Indonesia refused to recognize Israel and even barred Israeli citizens from entry, Singapore, despite pressure from its two powerful neighbors, chose to cooperate with Israel. The decision was not just pragmatic—it was also a recognition of their shared historical struggle as nations formed in response to ethnic persecution.

Despite their differing approaches—Israel as a national state united by history and religion, and Singapore as a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural nation forced to develop a model of coexistence—both countries demonstrated a fundamental truth: a lack of natural resources and a difficult geopolitical position are not insurmountable obstacles when a country prioritizes intelligence, innovation, and strategic thinking.

Why is this relevant? Because their difficult yet inspiring historical experiences offer valuable lessons. Belarus, positioned between major powers, must forge its own unique path—one that strengthens its sovereignty and transforms it into a thriving nation, worthy of emulation.

To be continued.